I was very pleased to participate in the Society for the Social History of Medicine conference this year, which took place from 11-14 July at Liverpool University. This report will particularly focus on the ways in which researchers discussed accessing and using archival resources, but I wanted to start by saying that the event was extremely well organised, and had a very international and welcoming feel. The standard of the papers was excellent and I thoroughly enjoyed myself and learned a great deal, so many thanks to all the organisers.

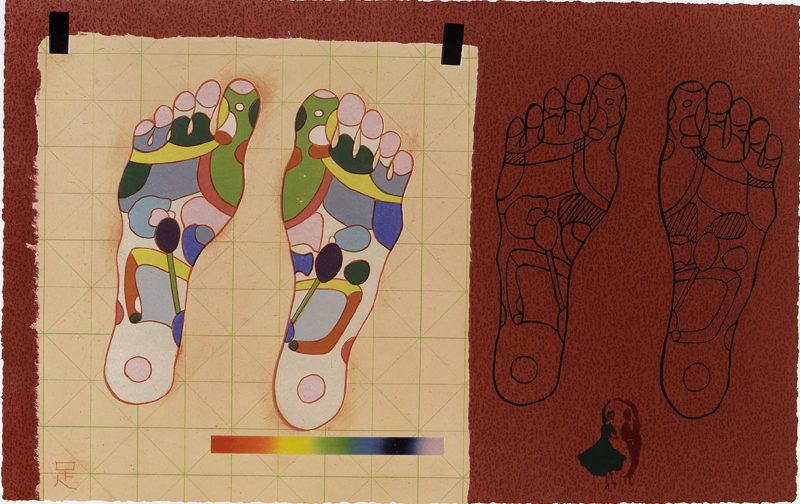

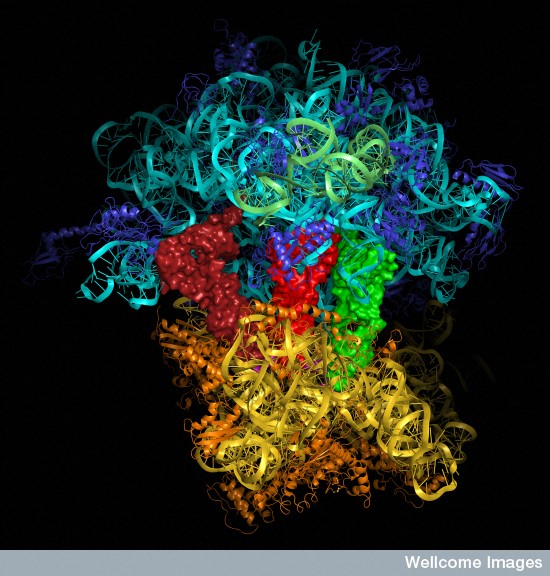

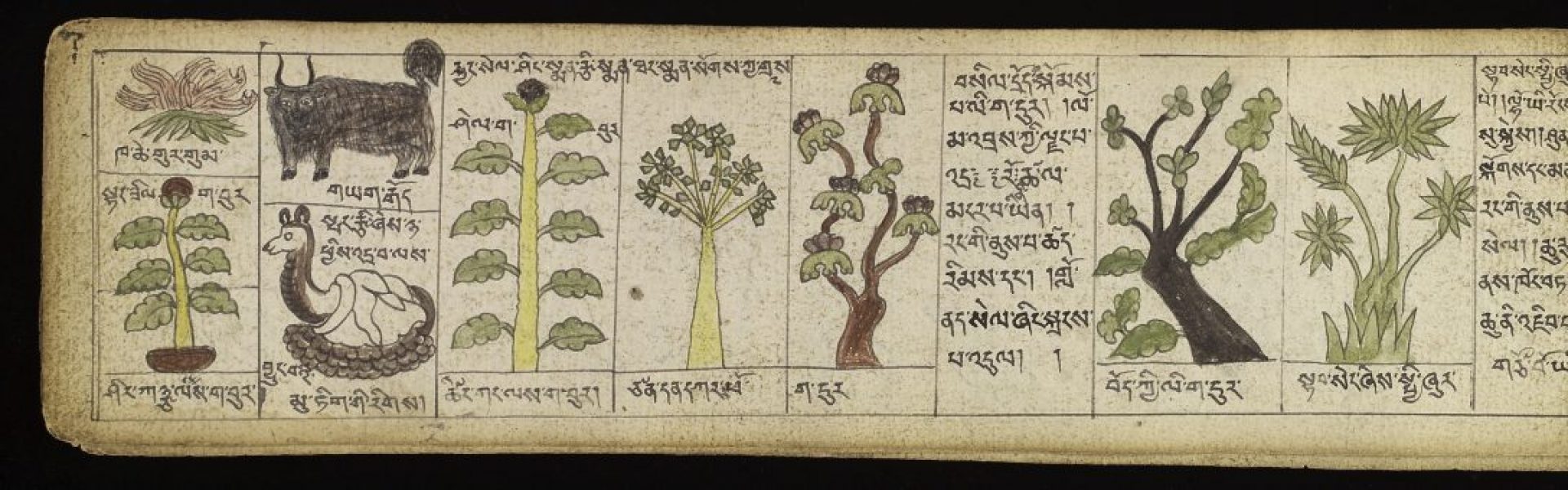

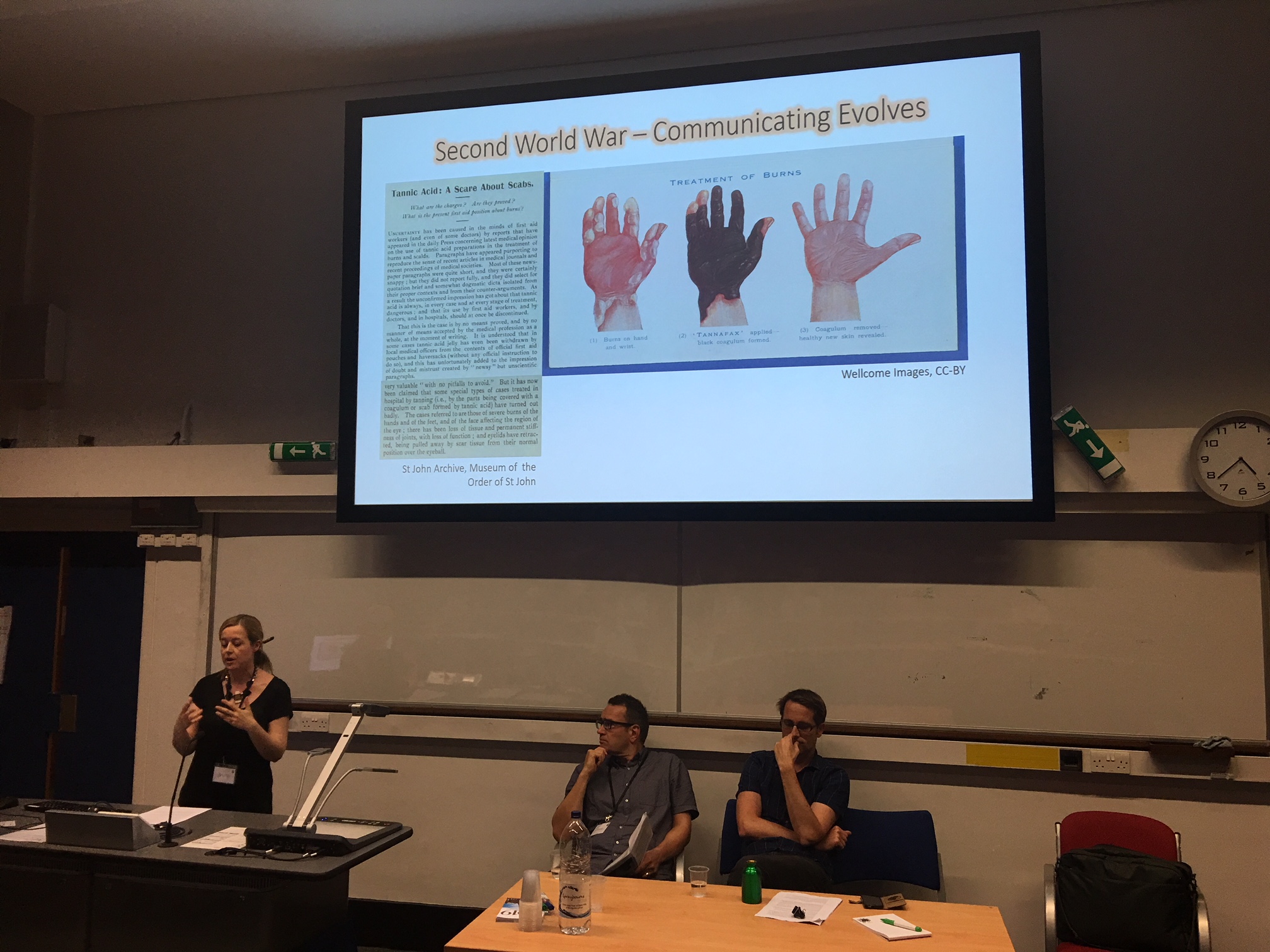

This was a very academic conference and by far the largest contingent came from higher education institutions with consumers, rather than custodians, of historical sources presenting the majority of the papers. As you would expect presenters talked a great deal about their use of archives, and referred to, and showed, documents and items including newspaper and magazine cuttings, letters, diaries, photographs, sketches, reports and pamphlets, held in a very wide variety of international archives, in their presentations. Archives were acknowledged and archivists often thanked for their support. It was interesting to see that presenters often displayed photographs alongside details of their Creative Commons licences, suggesting they are enjoying their increased ability to display archive images free of charge.

Researchers most commonly mentioned their use of big, national, UK archives. Kew often came up in connection with Department of Health records, and the British Library was clearly being used a great deal for research involving magazines and newspapers. I sat behind one delegate who was accessing the online catalogues of both these institutions while listening to a paper, trying to locate the sources mentioned and many people acknowledged and welcomed their increased ability to access important collections remotely. Some delegates, including myself and academics from Manchester University working on the NHS at 70 project, also talked of their work developing online archival collections, particularly in the field of oral history. The Wellcome Collection was also commonly cited and thanked as a research funder. Presenters mentioned hospital and university archives less commonly, although they are clearly using these resources. Key note speaker Ruth Richardson, author of ‘Death, Dissection and the Destitute’, spoke of her experience of being locked into St George’s archives as a result of chronic understaffing. There was no one to supervise her while she worked so they simply locked the doors to safeguard the documents.

In a similar vein, interestingly, although perhaps not surprisingly, many people expressed frustration about the lack of access to certain records, particularly papers relating to clinical matters, and the need for increasingly extensive and complex ethics reviews in order to unlock potentially sensitive material. Researchers commented that their inability to access such records often prevented them from representing the voices of patients in their work. There was some dismay, also, about the ongoing threat to records, even those held in national institutions such as Kew, especially in regard to NHS paperwork which is so copious that it apparently undergoes a regular process of filtering and destruction. People also spoke of records going missing, with one particularly interesting example provided by Hannah Mawdsley, PhD student at Queen Mary University, London, in her presentation on the 1918-19 Influenza Pandemic. She traced a box of letters giving first-hand accounts of the pandemic, which should have been in the Imperial War Museum archives, to the attic of the private home of Richard Collier, who originally collected the correspondence, just before house clearers went through the property’s contents.

One fascinating, and more surprising, revelation, was the inability to access, and sometimes even the complete lack of, private sector organisation archives, which should be key sources of information where companies have played a vital role in health related matters. For example it was shocking to hear that international consultancy firm, McKinsey, don’t have an archive at all, a policy designed to protect the privacy of their clients. Academics at Liverpool University described how this had been an issue in their attempts to research the 1974 restructuring of the NHS, and how they had tried to fill the gap in the sources by using duplicates of correspondence in government records and organising witness seminars involving former McKinsey consultants.

The panel that I attended that provided the richest information on potential audiences for medical archives focused on the campaign to secure acknowledgement for the damaging effect of Primados, a hormonal pregnancy test used from the 1950s to 1970s, on the development of foetuses. A journalist, a campaigner, a lawyer and a historian talked about their experiences of trying to access two depositaries, the Landesarchiv in Berlin and the Bayer / Schering Archives which hold the records of the pharmaceutical company that produced the drug, with varying levels of success. Although all researchers reported that the archives in Berlin had been helpful they also mentioned that at both institutions material was available very much at the archivists’ discretion, and that only the historian had had any success in accessing the records at the pharmaceutical company.

Given the nature both of delegates and of the research presented I would have thought that the SSHM conference would be an extremely fruitful event for promoting archival collections with a particular focus on health and medicine. However, with the exception of the Wellcome Collection, which was very well represented, very few archivists were present at the event. It may be useful and beneficial to both researchers and custodians to consider ways to use the conference to promote lesser known collections in future years.

Sarah Lowry

Oral History Officer, Royal College of Physicians of London

sarah.lowry@rcplondon.ac.uk