Cataloguing North Cambs Hospital

Posted onIn this post, Tiff Kirby, archives assistant at the Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire Archives, discusses her experience cataloguing the North Cambridgeshire Hospital records.

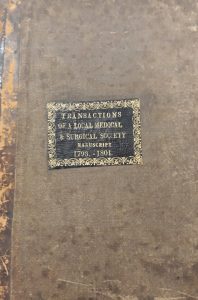

North Cambridgeshire Hospital, known as North Cambs, has served the people of Wisbech and North Cambridgeshire for a hundred and forty-four years. It was the initiative of philanthropist Margaret Trafford Southwell, who gave £8000 for the construction of the hospital, and £2000 as an endowment. It functioned as a voluntary hospital, paid for through subscriptions, until it became a General Hospital with the advent of the NHS. The records held at Cambridgeshire Archives span the period from before its construction to the 1990s, and they were catalogued in 2017.

During the record survey, it was evident that stickers surviving on the spine of some of the records, specifically volumes and substantial files, were evidence of a filing system. Unfortunately not enough of these stickers survived to reconstruct this system. To preserve it in an accessible way, the number on the sticker was included in the catalogue description so that this relationship between records was evident. In 1962 a survey of the hospital records was carried out by the then County Archivist. This showed that minutes and reports were kept in the secretary’s office, and patient registers and cash books kept in a nearby cupboard. This appeared to show sequences that, where possible, were followed while cataloguing. But these two systems conflicted. For example, in the 1962 survey, minutes of the Hospital Committee came before any other record, but in the sticker number sequence the first volume of the minutes was numbered 141. Files and other material held in four large boxes showed no apparent order, by chronology, subject, function or department, so original records of the endowment and construction of the hospital were held in a box with records of a time capsule excavation and application for trust status in the 1990s. The structure of the catalogue was based on function, but incorporated elements of original order and sequences wherever possible.

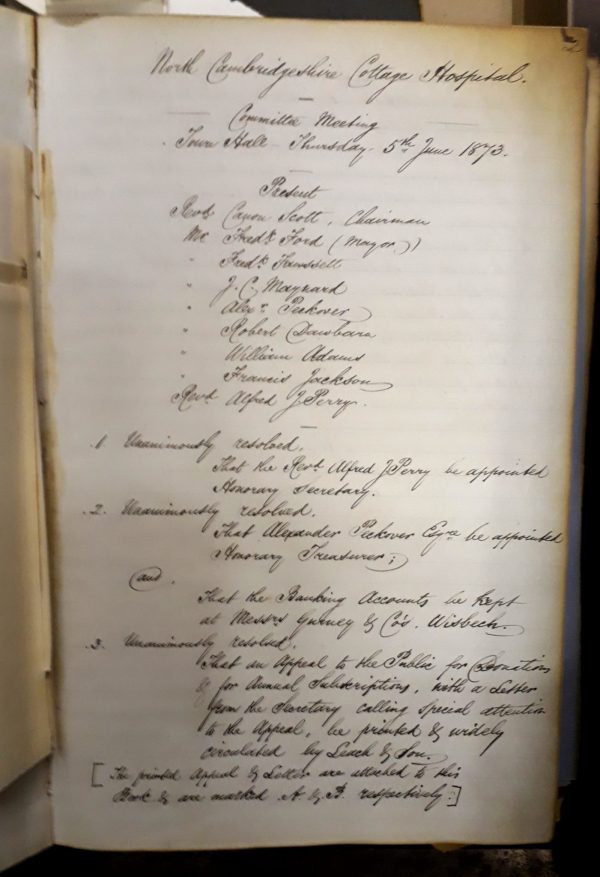

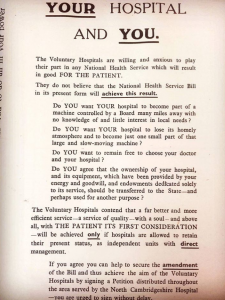

The collection includes the complete minutes of the Hospital Committee for the period North Cambs was a voluntary hospital. The Deed of Trust includes the constitution and provision for four Trustees, who were part of the management committee, along with 8 additional members who had subscribed a guinea a year for at least three years. The Committee met every Tuesday at midday. Details in the records include the purchase of a new chloroform inhaler at the beginning of the twentieth century, preparations for war such as blacking out and the purchase of gas masks, and controversy and opposition to the loss of the Hospital’s independent voluntary status with the advent of the National Health Service.

To develop services and expand capacity for increasing numbers of patients, North Cambs worked in partnership with other hospitals. Between 1925 and 1962 it worked with Addenbrooke’s hospital for the training of nurses, and from 1933 the provision of specialist services with a weekly Orthopaedic clinic by H.B. Roderick of Addenbrookes. 1946 – 9 saw the assistance of Addenbrooke’s to provide Medical and ENT Outpatient sessions. Lack of space post-war led to collaboration with the Clarkson hospital in Wisbech, which supplied two post-operative wards, enabling North Cambs to increase the number of surgeries.

From its opening in 1873 to the introduction of the NHS, North Cambs was governed by the Committee formed at the foundation of the hospital. From 1949 it was developed into a General Hospital providing a full range of specialist services, and was part of Peterborough Area Hospital Management Committee. In 1953 Peterborough Hospitals separated from North Cambridgeshire, and the hospital came under North Cambridgeshire Hospital Management Committee. In 1974 the Regional Hospital Boards were abolished and North Cambs came under West Norfolk and Wisbech Health Authority. From 1982 to 1990 the hospital came under the West Norfolk and Wisbech Health Authority Unit Management Team. In 2002 the Regional Health Authorities were replaced with Strategic Health Authorities. Today North Cambs is administered under Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust.