In this post, Tiff Kirby, archives assistant at the Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire Archives, selects some of the notable items relating to history of medicine within the archives.

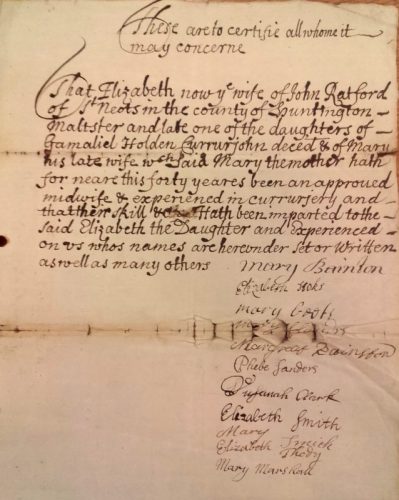

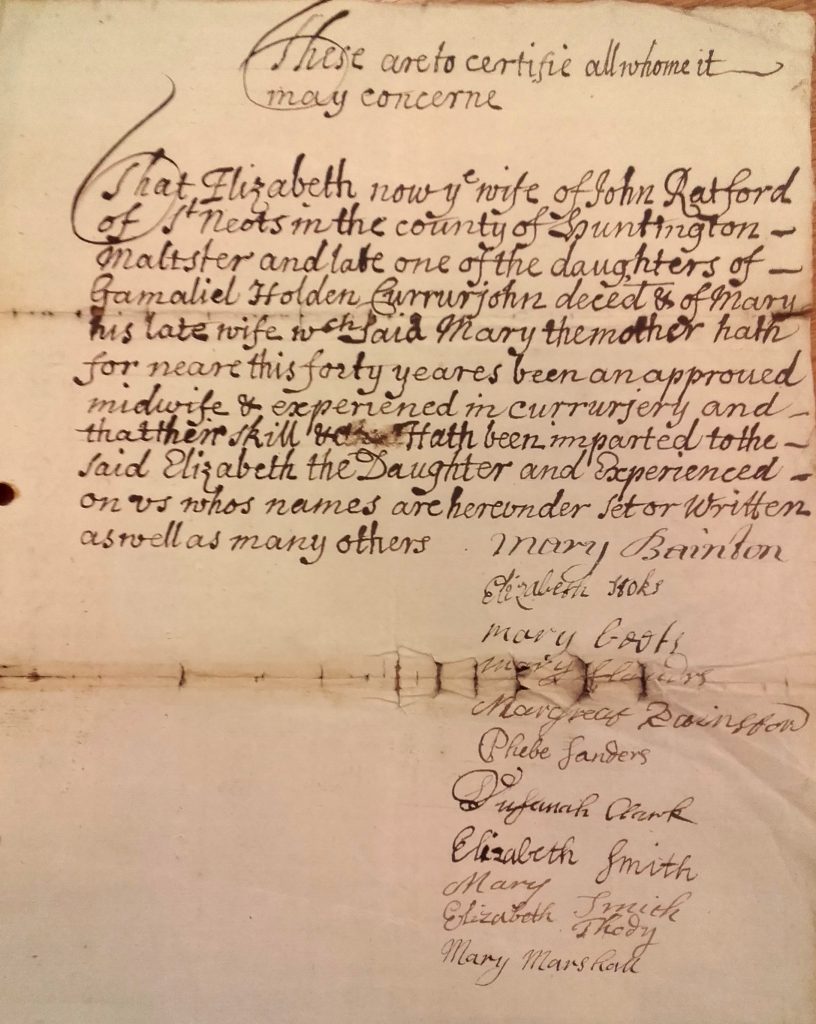

- Midwife Certificate of Elizabeth Ratford, 1717, AH27/6/271/278 Huntingdonshire Archives

From the sixteenth century, the Church certified both surgeons and midwives, and certificates from the Archdeaconry of Huntingdon are held at Huntingdonshire Archives. This certificate tells us Elizabeth Ratford’s mother was a midwife, and her father a surgeon, and that she learned her medical skills from her family. Other women testify to her expertise, and appear to have signed their own names – these are likely to have been other midwives. The certificate emphasises Elizabeth’s mother, who was for nearly forty years an approved midwife, and experienced in surgery.

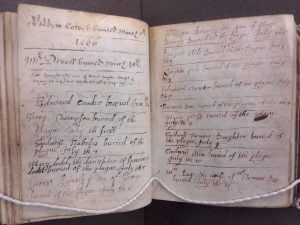

- Composite Parish Register of All Saints Parish Church, Cambridge, 1635 – 1702, P20/1/2 Cambridgeshire Archives

This register is very small, but its contents for the year 1666 trace the epidemic of plague through the parish, with page after page of deaths. Beginning with George Thompson, 95 people died between the 1st July and the 26th November. While cause of death was not routinely recorded in parish registers, ‘buried of the plague’ is written next to the entries at the beginning, becoming increasingly abbreviated, until simply a ‘p’ is written against the final burial.

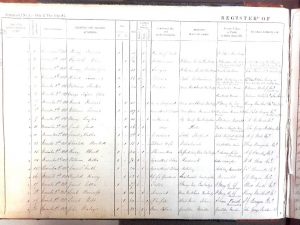

- Fulbourn Hospital Admission Register, November 1858- December 1870, KHF/3/1/1/1

The case notes of the earliest patients at Fulbourn Hospital (originally called the County Pauper Lunatic Asylum for Cambridgeshire, the Isle of Ely and the Borough of Cambridge) were destroyed by fire in the 1940s, which makes the earliest admission register particularly important. The first page records that Elizabeth Pain, a needlewoman from the Parish of St Andrew the Less in Cambridge, was admitted with mania of unknown cause. Elizabeth is indicated to be in otherwise good health, but we can see in the far-right hand column that the outcome wasn’t discharge and recovery, but that she died there in 1896 having spent decades in the Asylum. There are a variety of patients, on the same first page a lawyer, a shoemaker, a child of nine, with the largest group being labourers. Most admitted are described as having mania, melancholia, dementia and epilepsy, although these terms were not necessarily used consistently and changed their meaning over time.

- Transactions of the Huntingdon Medical and Surgical Society, 1793 – 1801, 4715

This volume shows the shift towards medical professionalisation, and an emphasis on scientific method. The physicians share cases, observations and best practice, such as how to use pulleys for shoulder dislocations. One of the most remarkable cases is that of John Gillett, a wagoner from Baldock who contracted rabies. Having been bitten by a dog in December, he himself made the connection to the bite when he became ill on the 7th May. He then suffered extreme hydrophobia, unable to consume any liquids, the closest he could bear was redcurrant jelly. Despite every effort by the attending physician, John Gillett died on the 9th May. In the physician’s observations he identifies the disease as a virus, although his understanding of this would have been an infectious substance produced by a diseased body. He notes the time interval between the bite and the symptoms, and believes this was because it took time for the virus to reach the heart. We know in rare cases rabies may not produce symptoms for over a year, because it takes time for the disease to reach the central nervous system. He talks of the importance of “regular and well conducted experiments,” to understand the disease in dogs, and in the meantime, they must use the little knowledge they have to establish “data.” While concluding his observations he says, “it surely behoves us all to strike out new paths for ourselves form’d on the most rational theories.”